Canadian American Common Law Status

Two weeks after border officers forced Canadian Stephen Barkey and American Cathy Kolsch to separate at the Canada-U.S. border, the couple has reunited.

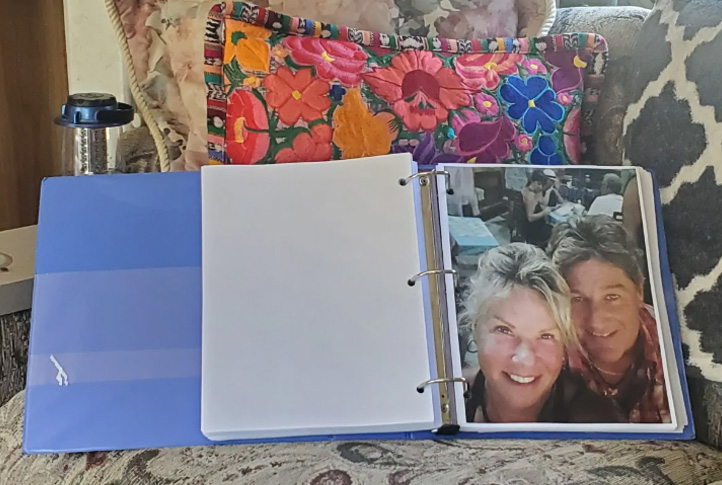

“We can’t stop smiling and just looking at each other,” said Kolsch, 61. She’s currently quarantining with Barkey, 65, in their recreational vehicle (RV), which is parked at a friend’s farm in Grenfell, Sask., located about 125 kilometres east of Regina.

It’s been a difficult journey for the couple, who has struggled to prove their common-law status to Canadian border officers. They said they finally won their case by spending $1,500 to hire a lawyer, who compiled a 250-page document detailing their life together.

“It was so painful,” said Kolsch of their ordeal. “My heart hurts for the [couples] who can’t get back together.”

To help stop the spread of COVID-19, Canada restricts foreigners from entering the country for non-essential travel. The Canada-U.S. land border also remains closed to non-essential traffic.

Last month, Canada loosened its travel restrictions to allow foreigners to visit immediate family in Canada — including spouses and common-law partners.

To qualify as common law, couples must have lived together for at least a year and prove it with documentation, such as shared household bills, or a joint mortgage or lease.

The rules have led to frustration and heartache for couples who can’t easily prove their common-law status.

‘I cried all the way’

Kolsch and Barkey said they’ve lived together for a year-and-a-half in their RV, dividing their time mainly between California and Barrie, Ont. As a result, they don’t have shared, monthly household bills or a mortgage.

The couple had been living in their RV in the U.S. when they first tried to cross the border from North Dakota into Saskatchewan on June 22.

Kolsch was denied entry into Canada, because the couple didn’t have the right documentation to prove that they’re common law.

Then, when they turned back to re-enter the U.S., Barkey was denied entry because the U.S. land border is now closed to Canadian visitors.

Consequently, the couple was forced to separate and retreat to their respective countries.

“I drove away and I cried all the way,” said Barkey, who took the RV to Grenfell.

Canadians can still fly to the U.S., but Barkey was too afraid to try, concerned he has been flagged after being denied entry at the U.S. land border.

Desperate for a resolution, the couple hired a Canadian immigration lawyer who worked with them to compile 250 pages worth of documents into a binder detailing their year-and-a-half together.

It included a timeline, date-stamped photos, receipts from RV campgrounds, testimonial letters from friends and a previous CBC News article detailing the couple’s struggle to prove their common-law status.

Kolsch then tried to enter Canada again, two weeks later on July 8. This time, she said she won over a border officer with the binder.

“He said, ‘I can see what you were doing here with the lawyer papers, the timeline, the pictures and the article. I know what you’re saying is truthful.’

“I let out a big sigh and tears flowed.”

The couple’s lawyer, Ali Esnaashari, suggested the Canadian government adopt more flexible common-law rules, so committed couples can more easily prove their status.

“If the goal is to reunite immediate family members and that’s why it’s there, then we need to have a more broader interpretation, more flexible interpretation of what we’re considering common law.”

Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) told CBC News the onus is on couples to prove they’ve been living together for at least one year.

“It must be established in each individual case, based on the facts,” said CBSA spokesperson Jacqueline Callin in an email.

1-year ban at the border

Kolsch and Barkey won their battle, but another cross border couple’s struggle to prove their common-law status has ended in defeat.

American Joseph Norris of Malone, N.Y., said he and his Canadian partner, Andrea Parraga of Ottawa, have lived together for at least one year. However, they don’t have shared household bills, because they each own a home in their respective countries. Malone is about 125 km southeast of Ottawa.

Norris, 45, tried to enter Canada at the Cornwall, Ont., crossing on June 25, but said he was denied entry because he didn’t have correct documentation.

He was told he needed a shared mortgage or lease agreement, or an official document certifying the couple was common law, said Norris.

So he dug up a common-law union document on the Canadian government’s website.

Five days later, on June 30, Norris tried to cross the border again so he and Parraga, 46, could sign the document together and get it verified. He thought his trip would be considered essential travel.

But it wasn’t. According to CBSA documents, Norris was denied entry again, and this time barred from entering Canada for one year.

“I was just beside myself. I couldn’t believe that this was happening,” he said.

CBSA said that when a foreigner doesn’t meet the requirements to enter Canada during the border closure, they run the risk of receiving a one-year ban if they try to re-enter.

Norris said he was never warned of this consequence and was just trying to get the evidence required to reunite with his partner in Canada.

“In these sad times, this was just another disheartening blow in an already horrible situation.”

The Canada-U.S. land border remains closed to non-essential traffic until at least Aug. 21. But for Norris, it remains closed until July 2021.

Migration Law Immigration Lawyers

Migration Law Immigration Lawyers